We think God will hear our heart’s cry if only we can sanitize it. But in the act of sanitization, we prove we do not trust him, as if he can only handle the sugar-coated prayers.

She had beaten leukemia when she was seventeen, then fought off breast cancer at thirty-two. By now, she and George were full of faith, and her peace was genuine. We soon discovered, however, that those earlier battles had taken a great toll on her body. A person can only handle so much radiation poisoning over her lifetime. Karen’s body had already taken all it could bear. This time, the doctors could not offer much help or much hope. All we could do was pray.

Prayer used to feel like a power option. Now it was a meager last resort.

It wasn’t George and Karen’s first rodeo, but it was mine. Thirty years of life unstained by serious hardship, and now in three months, three blows. First my sons, now my sister.

My memories blur together after that. There were meetings and cold rains and blank stares, stacks of firewood, and piles of unspoken fears. How long they went unspoken, I can’t say. It could have been days or weeks, but I remember the slow churning in my gut that so often accompanies quiet resentment.

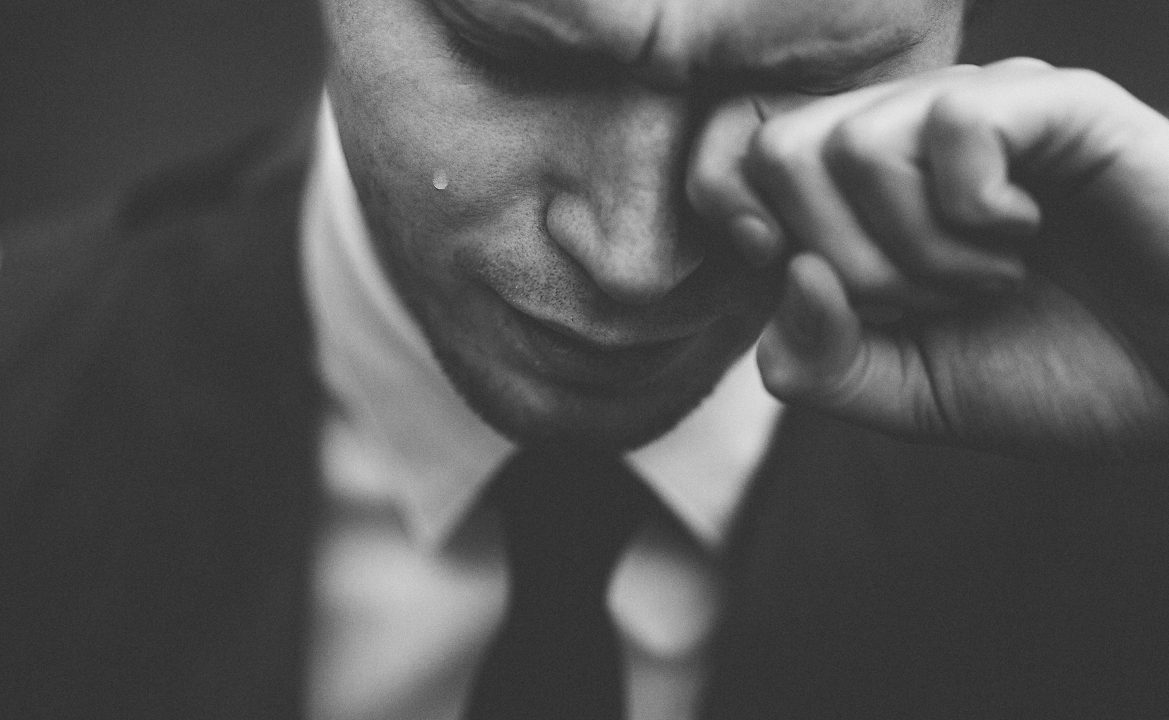

In essence, I gave God the silent treatment. But if I thought there was any power in it, I was wrong. It only made the pain more acute. The human mouth is, among other things, an effective pressure-release valve. Keep it closed too long, and the burning beneath will become unbearable. It’s true of human relationships, and it’s also true of prayer. Even David the psalmist, the author of the church’s most enduring prayer book, attempted to give God the cold shoulder once, and it didn’t work for him, either:

I was mute and silent;

I held my peace to no avail,

and my distress grew worse.

My heart became hot within me.

As I mused, the fire burned;

then I spoke with my tongue.

Psalm 39:2-3, ESV

When he couldn’t bear it any longer, he finally did speak. The rest of his psalm is a blaze of confession, accusation, and distress. David was renowned for his fire, and he never could hold it in for very long. Passion—sometimes for battle, sometimes for women, sometimes for God—permeated him. When the ark of the covenant returned to Jerusalem, he danced in his skivvies. When his would-be murderer died, he wept openly. When his enemies threatened him, he tried to pray down lightning. And when he felt abandoned by God, he turned his head to the sky and screamed,

Why are You so far from helping Me,

And from the words of My groaning?

O My God, I cry in the daytime, but You do not hear.

Psalm 22:1-2

We don’t like such psalms nowadays. We often skip past compositions like these in favor of greener pastures. These psalms are too dark. Too Old Testament.

That’s not the main reason we shy away from them, though, and we know it. The real reason is our religious decorum—our inexplicable thirst to hide our faces from our Creator. It is one thing to finally face the pains inside ourselves; it is another thing entirely to bring those pains to the altar of confession. Just who do we think we are, anyway? Who did David think he was, shoving his fist into the sky like that? Nobody wants to hear him say to God,

Attend to me, and hear me;

I am restless in my complaint, and moan noisily.

Psalm 55:2

We want the safe shepherd boy, the cute little slinger who sometimes played the harp for the grown-ups. Give us the praise anthems of the poet, the lover, the slayer of giants, and let us sing verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and bridge. Then we’ll change keys and sing the chorus again, this time with more feeling. The mainliners will nod gravely, the evangelicals will sway, and the charismatics will two-step in the aisles, because the psalms of praise are all of our inheritance. As for the desolate prayers, we have no affinity with them.

The Bible’s songbook, however, is littered with enough of these sentiments to make us all blush. We cannot ignore them. These are not sanitized sonnets for Sunday; these are poems that bleed.

David wasn’t the only one who wrote such scandalous stanzas, either. His fellow songwriters, the Sons of Korah, gave us this line:

Awake! Why do You sleep, O Lord?

Arise! Do not cast us off forever.

Why do You hide Your face,

And forget our affliction and our oppression?

Psalm 44:23-24

And Job, after he had lost everything, lashed out at God in an even more striking way:

Will You never turn Your gaze away from me,

Nor let me alone until I swallow my spittle?

Have I sinned? What have I done to You,

O watcher of men?

Why have You set me as Your target,

So that I am a burden to myself?

Job 7:19-20, NASB

My own complaint didn’t go so far as Job’s. Not only was his crisis many times heavier than mine, but I didn’t actually believe God was targeting me—how could I after his whispers about my sonship? And yet in one sense, that was part of the problem. If he was my Father who only wanted the best for me, why wasn’t he stepping in? It made no sense. He had all the power in the universe, but he wouldn’t wield it.

Why doesn’t he step in? Isn’t that the question we’re all asking? Is it because he can’t, or because he won’t? After that, the accusations cascade:

Don’t you see me, Jesus?

Can’t you tell I’m hurting?

Why me? Why now?

What have I done wrong?

For my part, I thought I had been more or less obedient to God. I had followed the path he laid out for me. I had dedicated my life to explaining and defending his goodness. And yet here I was, forgotten and out of favor, feeling a bit like Jeremiah at his angriest:

You pushed me into this, God, and I let you do it. . . . And now I’m a public joke.

Jeremiah 20:7-8, MSG

The frustrations are already there inside us, see. The doubts and disappointments, the accusations against God often lie in wait, covered in platitudes and postured peace. We know they are there, but we tell ourselves that it’s all right. Such thoughts are out-of-bounds, but as long as we can smother them with enough praise the Lords, they are harmless. We are wrong, though. These hanging questions are tumors feasting on our nerves and poisoning our trust.

This is the tragedy of our curious decorum. We think we are being respectful. We think God will hear our heart’s cry if only we can sanitize it. But in the act of sanitization, we prove we do not trust him, as if he can only handle the sugar-coated prayers.

Thus, we hide our faces behind veils to protect our Savior from the ugly, muddy truth of our souls, and in doing so we defer intimacy until the next life. Only in the great by-and-by, when our sharp edges are dull enough and our fires have sufficiently cooled, can we let him hear the full and unedited truth—the same truth he’s seen lying in our hearts since the day we learned to feel.

I’m not advocating transparency for its own sake. I’m advocating transparency as a first step toward spiritual healing. If we’ve come to terms with our broken places, we do not have to hide them from God. In fact, we must not.

Honesty with God is not only a better policy than hiding but also, I believe, more biblical. It was God’s best friends, after all, who seemed to be the most blunt in prayer. David, Job, and Jeremiah we’ve already mentioned. But didn’t Abraham himself haggle over the distraction of Sodom? And didn’t the law-giver Moses do the same over Israel? Didn’t Jacob face off against God in a midnight wrestling match? Part of what made the heroes of the faith heroes was the boldness they displayed before a powerful and often terrifying God.

If that isn’t enough, consider this: Jesus himself prayed exactly this way. While hanging on the cross, he cried out to his Father with the words of one of David’s most brutal, honest psalms:

My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?

Matthew 27:46; see also Psalm 22:1

Yes, in the land of unanswered prayer, we must follow Christ even in this way. That is why David urged us, “Cast your burden on the Lord, and He shall sustain you” (Psalm 55:22).

Cast it. Hurl it. Chuck it. Don’t hide it, and don’t lay it there delicately. God is not a child in need of sheltering. So give it to him, however seemingly toxic. It will feel audacious and improper to address a king this way. But you are not some random peasant; you are his son. His daughter. His beloved. So take aim, friend.

Tell him the truth.

See Genesis 18:16-33; Exodus 30:30-32; Exodus 32:7-14; and Genesis 32:22-32, respectively.

Aching Joy Following God through the Land of Unanswered Prayer by Jason Hague

When his oldest son was diagnosed with severe autism, pastor Jason Hague found himself trapped, stuck between perpetual sadness and a lower, safer kind of hope. This is the common struggle for those of us walking through the Land of Unanswered Prayer. Life doesn’t look the way we expected, so we seek to protect ourselves from further disappointment.

But God has a third path for us, beyond sadness or resignation: the way of aching joy. Christ himself is with us here, beckoning us toward the treasures hidden in the darkness.

Aching Joy is an honest psalm of hope for those walking between pain and promise: the aching of a broken world and the beauty of a loving God. In this place, rather than trying to dodge the pain, we choose to feel it all—and to see where Jesus is in the midst of struggle. And because we make that choice, we feel all the good that comes with it, too.

This is Jason’s story. This is your story. Come, find your joy within the aching.